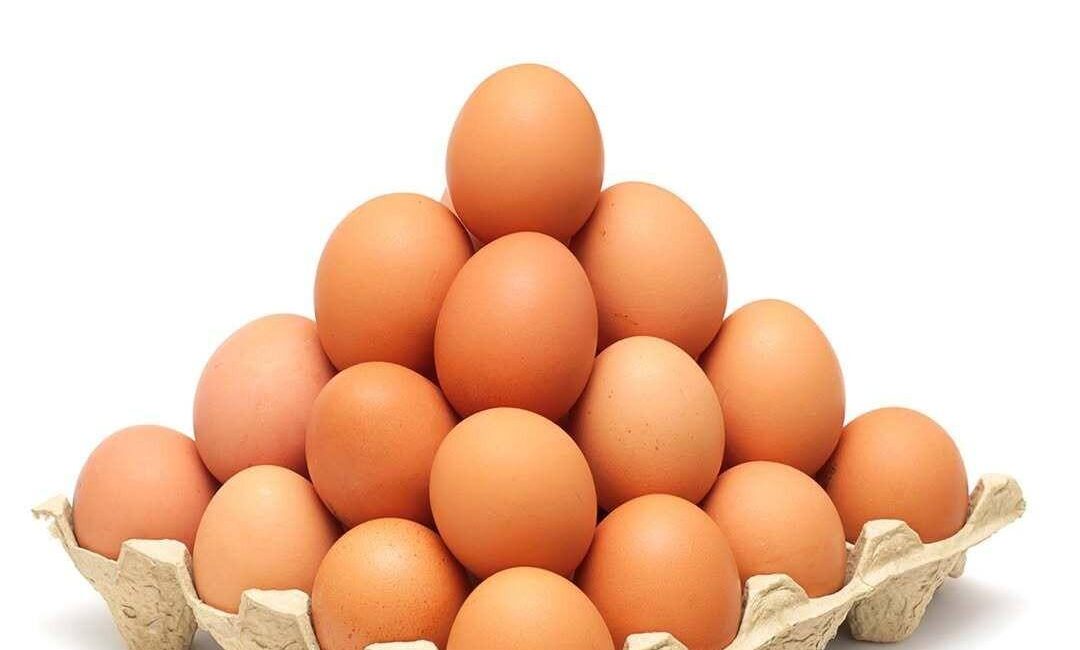

At first glance, it seems like a child’s riddle. A simple image of brown eggs arranged in a pyramid-like structure. A neat, orderly triangle. And a straightforward question:

“How many eggs are in the photo?”

You look once. You look again. Maybe you think 10. Maybe 20. Perhaps you try to estimate the hidden layers behind the ones you can see. Maybe you start applying geometry, like calculating rows in a pyramid. But the question is deceptively simple:

“How many eggs are in the photo?”

It doesn’t ask how many you think are there. It doesn’t want to know what’s hidden in the back. It’s not about assumptions. It’s about perception.

And that’s what makes this puzzle so brilliant.

This challenge isn’t a math problem — it’s a test of visual cognition, attention to detail, and mental clarity. It’s a lesson in how we process reality, and more importantly, how often we get it wrong.

Why This Puzzle Feels So Tricky

The image shows a group of brown eggs arranged in a triangular or pyramid shape. Some eggs are clearly visible. Others are partially visible, peeking out from behind or beneath other eggs.

You might be tempted to assume the full pyramid structure — imagining layers of eggs going back in space, stacked like cannonballs.

But that’s where most people go wrong.

Because the question is very specific: “How many eggs are in the photo?”

Not how many you think are there. Not how many could be. Only those you can see.

And when you count the visible eggs — whether fully or partially shown — the answer is:

16 eggs.

How the Puzzle Works: A Matter of Perception

This puzzle doesn’t test your math skills. It tests something far more subtle: your ability to interpret visual data without falling prey to assumptions. It plays with your brain’s tendency to:

- Fill in incomplete patterns

- Assume depth where none exists

- Overthink a simple question

If you carefully count only what is visible — including eggs that are partly hidden — you’ll reach the correct number. No guessing. No 3D extrapolation. Just pure observation.

This is the kind of brain teaser that separates the quick thinker from the accurate one. And it reveals more about your mental habits than you might realize.

Why So Many People Get the Wrong Answer

The trap is simple: your brain wants to complete the picture.

When you see a few eggs, it assumes the presence of more. That’s not a flaw — it’s how human vision evolved. Our minds are designed to recognize patterns quickly and fill in missing data. This helps us survive in complex environments, but it also makes us vulnerable to false assumptions.

Common Wrong Answers:

- 10 eggs – because people count rows and assume a small base.

- 20 or more – guessing at hidden layers.

- 18 or 21 – including “invisible” eggs based on geometry.

But all of these answers ignore the key instruction: only count the eggs you can actually see.

This isn’t about 3D thinking. It’s about visual clarity and mental discipline.

Visual Cognition: How Your Brain Processes What You See

The human brain processes visual information at an astonishing rate — up to 13 milliseconds per image. But speed often comes at the cost of accuracy.

When you look at the egg image, your brain’s visual cortex processes the shapes and arrangement, while your prefrontal cortex begins interpreting the structure based on past experience.

That’s why many people automatically start calculating the number of eggs in a theoretical pyramid — not in the photograph.

This is known as a cognitive bias — specifically, pattern completion bias. Your brain isn’t being lazy; it’s just trying to help. But in this case, that help leads to the wrong answer.

The Role of Attention to Detail

Attention to detail is a key skill in professions like:

- Medical diagnostics

- Engineering

- Financial analysis

- Aviation

- Software quality control

In each of these fields, missing a small but critical detail can lead to major errors.

This egg puzzle is a miniature version of the same challenge: Can you focus on only the available data without making assumptions?

People with high attention to detail tend to pause, analyze, and question what they’re seeing. They don’t rush to conclusions. And more often than not, they get the answer right.

Click page 2 for more